Pioneers of Positive Psychology

Several humanistic psychologists, most notably Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Erich Fromm, developed theories and practices related to human happiness and flourishing. Nonetheless, positive psychology scholars have recently found empirical support for those approaches and advanced their ideas. Positive Psychology owes its success to the efforts and contributions of numerous pioneers (other than Martin Seligman), such as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Christopher Peterson, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Barbara Fredrickson, Ed Diner, Paul Wong and many more scientists who have worked hard to bring people happiness and well-being.

Abraham Maslow

Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970) was an American psychologist best known as one of the founders of humanistic psychology. He created Maslow's hierarchy of needs and emphasised the importance of focusing on people's positive qualities rather than treating them as a "bag of symptoms."

Maslow felt that Freud's psychoanalytic theory and Skinner's behavioural theory were too focused on the negative or pathological aspects of existence and neglected human beings' potential and creativity. He wanted to know what constitutes positive mental health and urged people to acknowledge their basic needs before addressing higher needs and, ultimately, self-actualisation.

To prove that humans are not blindly reacting to situations but trying to accomplish something significant, Maslow studied mentally healthy individuals instead of people with serious psychological issues. He focused on self-actualising people and argued that self-actualising people indicate a coherent personality and represent optimal psychological health and functioning.

Beyond fulfilment of needs, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as Peak Experiences, which are profound moments of love, understanding, happiness or rapture, during which a person feels whole, alive, self-sufficient and yet a part of the world, more aware of the truth, justice, harmony, goodness, and so on. Self-actualising people are more likely to have peak experiences. In other words, these "peak experiences" or states of flow (as Csikszentmihalyi called them) are the reflections of realising one's human potential and represent the height of personality development.

Maslow referred to his work as “positive psychology”, which (since 1968) has influenced the development of modern Positive Psychotherapy. Since 1999, Maslow’s work has revived interest among positive psychology pioneers, such as Martin Seligman. Maslow’s work has also inspired transcultural humanistic-based psychotherapy, which was founded by Nossrat Peseschkian.

Maslow is also known for Maslow's hammer, popularly phrased as "if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail" (from his book The Psychology of Science, published in 1966). In the 1950s, Maslow became one of the founders and a driving force behind the humanistic psychology school of thought. His theories, including the hierarchy of needs, self-actualisation and peak experiences, became fundamental subjects in the humanist movement.

Most psychologists of his time focused on neurotic and negative aspects of human nature that were considered abnormal. On the other hand, Maslow shifted his focus to the positive aspects of mental health. His interest in human potential, seeking peak experiences and improving mental health by pursuing personal growth had a lasting influence on the science of psychology and most therapeutic approaches in mental health practices.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow first introduced the hierarchy of needs in a paper about human motivation in 1943. He later extended the idea to include his observations of humans' innate curiosity and created a classification system that reflected the universal needs of society as its base, proceeding to more developed motivations. This perspective implies that for the motivation of the next stage to arise, the previous stage must be satisfied first. Additionally, each of these individual levels contains a certain amount of internal resolution that must be met for an individual to complete that level. The goal in Maslow's theory is to attain the fifth and final stage of self-actualisation.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Every person is capable and desires to move up the hierarchy toward self-actualisation. Unfortunately, progress could be disrupted when someone fails to achieve lower-level needs. Adverse life experiences, such as divorce and loss of a job, may cause an individual to fluctuate between levels of the hierarchy. Therefore, not everyone will move steadily through the hierarchy and may move back and forth between the different levels of needs.

In a nutshell, Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a motivational theory containing a five-tier model of human needs. Needs lower down in the pyramid must be satisfied before individuals attend to needs higher up. From the bottom of the hierarchy upwards, the needs are physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation.

Maslow's theory was fully expressed in his 1954 book: Motivation and Personality. The hierarchy remains a popular framework in sociology, psychology and management training. Maslow's hierarchy has been revised over time. The original hierarchy states that a lower level must be completely satisfied and fulfilled before moving on to a higher pursuit. However, nowadays, many scholars prefer to think of these levels as interrelated criteria rather than sharply separated levels.

The most fundamental and essential four layers of the pyramid contain what Maslow called "deficiency needs" (or d-needs): self-esteem, friendship and love, security and physiological needs. If these needs are not met (except for physiological needs), there may not be a visible indication of their deficit, but the individual will feel inadequate, anxious and tense. Maslow also coined the term "meta motivation" to describe the motivation of people who go beyond the scope of the basic needs and strive for constant betterment.

The human brain is a complex system and has parallel processes running simultaneously. Thus, many different motivations from various levels of Maslow's hierarchy can occur at the same time. Maslow spoke clearly about these levels and their satisfaction with terms such as "relative", "general" and "primarily", stating that a certain need may dominate at certain points in life, but he focused on identifying the basic types of motivation and the order in which they tend to show up.

Physiological needs include homeostasis, health, food and water, sleep, clothing and shelter. Safety and security needs include personal security, emotional security, financial security, health and well-being, and safety against accidents or illness and their adverse impacts. Social belonging needs consist of friendships, intimacy and family.

Humans need to feel respected, which also includes having self-esteem and self-respect. Esteem represents the desire to be accepted and valued by others. People often engage in an activity (profession or hobby) to gain respect, recognition and a sense of value. Low self-esteem (inferiority complex) may result from imbalances of expectation and reality and any stage in life. Maslow identified two types of esteem: a "lower version” and a "higher version”. The lower version of esteem is the need for respect from others and may include a need for status, recognition, fame, prestige and attention. The higher version manifests itself as the need for self-respect and can consist of strength, competence, mastery, self-confidence, independence and freedom.

Although recent research appears to validate the existence of universal human needs, the hierarchy proposed by Maslow is academically crucially contested. Nonetheless, it has widespread influence outside academia and as Uriel Abulof (senior lecturer of politics at Tel-Aviv University) argues, "the continued resonance of Maslow's theory in the popular imagination, however unscientific it may seem, is possibly the single most telling evidence of its significance: it explains human nature as something that most humans immediately recognise in themselves and others."

Self-actualisation/Transcendence

Maslow describes self-actualisation as the desire to accomplish everything that one can and become the most that one can be. Maslow believed that to understand this level of motivation (or need), the person must succeed in the previous needs and master them. Self-actualisation is understood as the goal or explicit motivation, where the earlier stages in Maslow's Hierarchy fall in line to facilitate it. Individuals motivated to pursue such goals seek and understand how their needs, relationships and sense of self are expressed through their behaviours.

Self-actualisation is the highest level in Maslow's hierarchy and refers to realising a person's potential (self-fulfilment and peak experiences). Maslow's idea of self-actualisation has been commonly interpreted as "the full realisation of one's potential" and of one's "true self." According to Maslow, a more explicit definition of self-actualisation is "intrinsic growth of what is already in the organism or more accurately of what is the organism itself”. Self-actualisation is growth-motivated rather than deficiency-motivated.

Self-actualisation occurs when people take full advantage of their talents while still being mindful of their limitations. This term is also used informally to refer to an enlightened maturity characterised by achieving goals, accepting oneself and an ability to self-assess realistically and positively.

In his later years, Maslow explored a further dimension of motivation while criticising his original vision of self-actualisation. He argued that people find their highest fulfilment in giving themselves to something beyond their ego (transcendence), such as altruism or spirituality.

Transcendence refers to the highest and most inclusive or holistic level of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means to oneself, significant others, other human beings, other species, nature and the cosmos.

Self-transcendence is a personal quality that involves extending our boundaries to include spiritual ideas, such as humanity and nature (the universe). Viktor Frankl wrote, "The essentially self-transcendent quality of human existence renders man to a being who reaches out beyond himself."

According to Dr Pamela G Reed (University of Arizona), self-transcendence is: “the capacity to expand self-boundaries intra-personally (toward greater awareness of one's philosophy, values and dreams), interpersonally (to relate to others and one's environment), temporally (to integrate one's past and future in a way that has meaning for the present), and trans-personally (to connect with dimensions beyond the typically discernible world).”

Further Reading

Maslow, A.H. (1943). "A theory of human motivation". Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.

Deckers, Lambert (2018). Motivation: Biological, Psychological, and Environmental. Routledge Press.

Maslow, A (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-041987-5.

Goble, F. (1970). The third force: The psychology of Abraham Maslow. Richmond, CA: Maurice Bassett Publishing.

Maslow, Abraham H. (1996). "Critique of self-actualization theory". In E. Hoffman (ed.). Future Visions: The unpublished papers of Abraham Maslow.

Abulof, Uriel (2017-12-01). "Introduction: Why We Need Maslow in the Twenty-First Century". Society. 54 (6): 508–509.

Garcia-Romeu, Albert (2010). "Self-transcendence as a measurable transpersonal construct" (PDF). Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 421: 26–47.

Carl Rogers

Carl Rogers (1902 – 1987) was an American psychologist and one of the founders of the humanistic approach to psychology. Rogers is the founding father of psychotherapy research and was honoured for his pioneering contributions (1956 & 1972) by the American Psychological Association (APA).

Rogers’s unique, person-centred approach to understanding personality and human relationships has been used in psychotherapy, counselling, coaching, education, business and other settings where rapport is essential. A person-centred approach, also known as Rogerian psychotherapy (since 1940) or person-centred psychotherapy, is a form of therapy (counselling or coaching) that seeks to facilitate clients’ self-actualising tendency (an inbuilt desire toward growth and fulfilment) through acceptance, unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding.

Rogers wrote his first book, The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child, in 1939, while working as a lecturer at the University of Rochester in New York. It was based on his experience in working with troubled children. He wrote his second book, Counselling and Psychotherapy, in 1942, when he was a professor of clinical psychology at Ohio State University. He also taught psychology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1957–63), during which time he wrote one of his best-known books, On Becoming Person (1961). His other books include Carl Rogers on Personal Power (1977) and Freedom to Learn for the 80s (1983). He wrote 16 books and many more journal articles describing his theories.

Rogers' theory of the self is humanistic, existential and phenomenological (study of things as they appear in our conscious experience) and was based on propositions that describe how individuals (organisms) exist in a continually changing world of experience (phenomenal field). This adaptable field is the "reality" of the individual who reacts to it as experienced and perceived. A portion of the total of this perceptual field gradually becomes differentiated as the self (I or me), with one basic tendency: striving to actualise, maintain and enhance itself, and as such, the behaviours of the organism are goal-directed attempts to satisfy the needs of the organism as experienced, in the perceived field.

In developing the self-concept, he saw conditional and unconditional positive regard as key. Those raised in an environment of unconditional positive regard can actualise themselves fully. Those raised in an atmosphere of conditional positive regard feel worthy only if they match some conditions (what Rogers described as conditions of worth) that have been laid down for them by others.

Rogers identified the "real self" as the aspect of one's being, established in the actualising tendency that follows organismic valuing (based on our inner nature and purpose) and needs and receives positive regard and self-regard. In other words, it is the "you" that you will become if all goes well.

On the other hand, to the extent that our society is out of sync with our actualising tendency, and we are forced to live with conditions of worth (including authenticity, autonomy, internal locus of evaluation and unconditional positive regard), and receive only conditional positive regard, we develop an "ideal-self". By ideal, Rogers means not real, which is always out of our reach, the standard we cannot meet. This gap between the real/authentic self and the ideal self, the "I am and the “I should be", is called incongruity.

For Rogers, the concepts of congruence and incongruence were crucial ideas. He believed that a fully congruent person is not at the mercy of experiencing positive regard. They can lead lives that are authentic and genuine. On the other hand, incongruent individuals, in their pursuit of positive regard, lead lives that include various fallacies and do not realise their potential. Conditions put on them by those around them make it necessary for them to give up their true, authentic lives to meet with the approval of others. They live lives that are not true to themselves and who they are. Rogers suggested that the incongruent individuals, who are always on the defensive and cannot be open to all experiences, are not functioning ideally and may even be malfunctioning.

Rogerian rhetoric is a conflict-solving technique based on seeking common ground instead of having a polarising debate. In Rogerian strategy, participants in a discussion collaborate to find areas of shared experience, allowing the speaker and the audience to open their worlds to each other. There is the possibility, at least, of persuasion in this attempt at mutual understanding. In this state of sympathetic understanding, we can recognise both the diversity of worldviews and our freedom to choose among them.

Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (1900-1980) was a German social psychologist and philosopher who fled the Nazi regime and settled in the US. He became one of the founders of The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry in New York and was associated with the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory.

After the Nazi takeover, Fromm moved first to Geneva and then to Columbia University in New York (1934). Together with Karen Horney and Harry Stack Sullivan, Fromm belongs to a Neo-Freudian school of psychoanalysis.

Fromm's books were known for their social and political commentary and philosophical and psychological underpinnings. Escape from Freedom (1941), known as Fear of Freedom in Britain, is viewed as one of the starting conceptions of political psychology. His second important work, Man for Himself, was an Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), which continued and enriched the ideas reflected in Escape from Freedom. These books outlined Fromm's theory of human character as a natural outgrowth of Fromm's view of human nature. Fromm's most popular book was The Art of Loving, an international bestseller first published in 1956. This book was a review and complemented the theoretical principles of human nature found in Fromm’s previous books.

“The situation of humankind is too serious to permit us to listen to the demagogues, least of all demagogues attracted to destruction or even to the leaders who use only their brains and whose hearts have hardened. Critical and radical thought will only bear fruit when blended with the most precious quality man is endowed with the love of life. ”

Central to Fromm's worldview was his interpretation of the Talmud (the primary source of Jewish laws) and Hasidism (a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in Ukraine during the 18th century – these days, most Hasidic Jews reside in Israel and the US). However, in 1926, Fromm turned away from orthodox Judaism and towards secular interpretations of scriptural ideals. Fromm was reportedly an atheist for the rest of his life but described his position as non-theistic mysticism (extraordinary experiences during alternate states of mind).

Beyond a simple condemnation of authoritarian value systems, Fromm used the story of Adam and Eve as an allegorical explanation for human biological evolution and existential angst. When Adam and Eve ate from the “Tree of Knowledge”, he interpreted that they became aware of themselves as beings separate from nature while still being part of it. Therefore, they felt "naked" and "ashamed". They had evolved into earthy human beings, conscious of themselves, their mortality and powerlessness before nature's forces. They were no longer united with the universe as they were in their instinctive, heavenly existence. According to Fromm, the awareness of humans as beings disunited from nature is a source of guilt and shame. He suggested that the solution to this existential dichotomy is to develop one's uniquely human powers of love and reason.

However, Fromm distinguished his concept of love from unreflective popular notions and Freudian paradoxical love. He considered love an interpersonal, creative capacity rather than an emotion. Fromm differentiated this creative capacity from what he thought to be different forms of narcissistic neuroses and sadomasochistic (sexual gratification from pain and humiliation) tendencies commonly held out as proof of "true love". Fromm viewed the experience of "falling in love" as evidence of one's failure to understand the true nature of love, which he believed had the common elements of care, responsibility, respect and knowledge. Fromm asserted that few people in modern society have respect for the autonomy of their fellow human beings, much less an objective understanding of what other people genuinely want and need.

Fromm suggested seven basic needs: 1) Transcendence, transcending our nature by creating and caring for people or things; 2) Rootedness, establishing roots, feeling at home in the world and being able to grow beyond the security of our home and establish ties with the outside world; 3) Sense of Identity, a sense of uniqueness, individuality, and selfhood; 4) Frame of Orientation, understanding the world and our place in it; 5) Excitation and Stimulation, striving for a goal rather than simply reacting; 6) Unity, oneness between a person and the nature and 7) Effectiveness, the need to feel accomplished.

Fromm's brand of socialism rejected both Western capitalism and Soviet communism, which he saw as dehumanising. He became one of the founders of socialist humanism, promoting the early writings of Marx and his humanist messages to the US and Western European public. For a period, Fromm was also active in US politics. He joined the Socialist Party of America in the mid-1950s. He did his best to help them provide an alternative viewpoint to McCarthyism trends (making accusations of subversion or treason without proper regard for evidence). This alternative viewpoint was best expressed in his 1961 paper “May Man Prevail? An Inquiry into the Facts and Fictions of Foreign Policy”.

Fromm was a co-founder of SANE in 1957 (the earlier name for Peace Action), inspired by the concepts introduced in his book: The Sane Society. The group aimed to alert people of the threat of nuclear weapons. Fromm's most robust political activism was in the international peace movement fighting against the nuclear arms race and the US involvement in Vietnam.

To Have or To Be (1976) was Erich Fromm’s last major work, where he argues that two ways of existence were competing for the spirit of humankind, having and being. The having mode looks to things and material possessions based on aggression and greed. The being mode is rooted in love and is concerned with shared experience and productive activity. The dominance of the having mode (as he argued in The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness) brought the world to the edge of disaster. Fromm argued that only a fundamental change in human character from a dominance of the having mode to the superiority of the being mode of existence could save us from a psychological and economic catastrophe.

Further Reading

Erich Fromm, [1973] 1992, The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, New York: Henry Holt.

Erich Fromm, [1955] 1990 The Sane Society, New York: Henry Holt.

Fromm, Erich "Escape from Freedom" New York: Rinehart & Co., 1941.

Fromm, Erich. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx & Freud. London: Sphere Books, 1980.

The Glaring Facts. "Erich Fromm & Humanistic Psychoanalysis Archived January 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine." The Glaring Facts, n.d. Web. 12 November 2011.

Funk, Rainer. Erich Fromm: His Life and Ideas. Translators Ian Portman, Manuela Kunkel. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003.

Martin Seligman

Martin Seligman (August 1942) is a professor of psychology and the director of Positive Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. Martin Seligman is a founding member of modern positive psychology (though Abraham Maslow coined the term). He was elected president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1998, when he used his inaugural speech to launch the positive psychology movement.

Seligman has written about positive psychology topics in books such as The Optimistic Child, Child's Play, Learned Optimism, Authentic Happiness and Flourish. His most recent book, The Hope Circuit: A Psychologist's Journey from Helplessness to Optimism, was published in 2018.

Seligman concluded that happiness has three dimensions (the Authentic Happiness Theory): Pleasant, Good, and Meaningful Lives. The pleasant life is realised if we learn to savour and appreciate basic pleasures such as companionship, the natural environment and biological needs. The good life is achieved through discovering our unique character strengths (virtues) and employing them creatively to enhance our lives. The meaningful life is a stage where we find a deep sense of fulfilment by using our unique strengths for a purpose greater than ourselves. Seligman's theory is brilliant because it reconciles two conflicting views of human happiness: the individualistic approach, which emphasises taking care of ourselves and nurturing our strengths, and the altruistic approach, which tends to downplay individuality and emphasises sacrifice for a greater purpose.

Seligman describes five factors of well-being (PERMA Well-being Theory): Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and purpose, and Accomplishment. Unlike the previous theory, where character strengths were relevant only for engagement, here, character strengths are relevant to maximising the well-being felt from all five factors. High levels of well-being lead to flourishing, which is described as thriving, being full of vitality and prospering both as individuals and groups.

Character Strengths and Virtues

One notable contribution that Seligman has made to positive psychology is his cross-cultural study, which created an authoritative classification and measurement system for human strengths. He and Christopher Peterson, a top expert in hope and optimism, worked to develop a classification system that would help psychologists measure positive psychology's effectiveness. They were surprised to find six virtues valued in almost every culture and cherished independently (not a means to another end). Our core strengths stem from these six classes of virtues (the highest human qualities) comprising more than twenty measurable character strengths.

Wisdom and Knowledge, which include Creativity, Curiosity, Judgement, Open-mindedness, Love of Learning, and Perspective.

Courage, which includes Bravery, Perseverance, Honesty, and Zest.

Humanity, which includes Love, Kindness, and Social Intelligence.

Justice, which includes Teamwork, Fairness, and Leadership.

Temperance, which includes Forgiveness, Humility, Prudence, and Self-regulation.

Transcendence, which includes Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence, Gratitude, Hope, Humour, and Spirituality.

Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (September 1934 – October 2021) was a Hungarian American psychologist who discovered and named the psychological concept of flow, a highly focused mental state conducive to productivity. He was a leading positive psychology researcher and has worked extensively on happiness, creativity and motivation. Czikszentmihalyi studied what makes people happy and pioneered the "experience sampling method" to discover what he called "the psychology of optimal experience," precisely speaking, the experience of flow.

Flow: The Science of Peak Performance

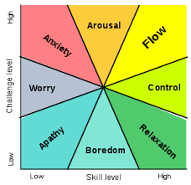

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described flow (1970s) as "being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away, and time flies. Every action, movement and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing music. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost.” Achieving flow can be a great way to make our activities more engaging and enjoyable. People often perform better and improve their skills when in a flow state.

In the state of flow, you feel completely at one with what you're doing; you are in total control, so-called “in the zone,” and in complete focus. Flow (or being in the zone) happens in those moments of exquisite attention and total absorption when you get so focused on the task at hand that everything else disappears, and all aspects of performance, mental and physical, go through the roof.

Csikszentmihalyi identified three causes for flow: immediate feedback, the potential to succeed and feeling engrossed in the experience. He described seven characteristic features of flow: 1) intense and focused concentration, 2) a merger of action and awareness, 3) clarity of goals (purpose and objectives), 4) loss of reflective self-consciousness, 5) a sense of agency or personal control, 6) distortion of temporal experience and 7) experiencing the activity as intrinsically rewarding (autotelic experience). Other researchers have validated and extended these ideas. Moreover, they confirmed that Csikszentmihalyi was correct in his word choice. “Flow” is indeed the proper term for the experience.

The state of flow emerges from a radical alteration in brain functioning. In flow, as attention heightens, the slower and energy-expensive extrinsic system (conscious processing) is swapped with far faster and more efficient processing of the subconscious, intrinsic system. The technical term for this exchange is “transient hypofrontality,” with “hypo” (meaning slow) being the opposite of “hyper” (fast) and “frontal”, referring to the prefrontal cortex, the part of our brain that houses our higher cognitive functions. This transition is one of the main reasons flow feels flowy because any brain structure that would hamper rapid-fire decision-making is shut off.

Self-monitoring (self-consciousness) is the voice of doubt, the defeatist nagging of our inner critic. Since “flow” is a fluid state, where problem-solving is nearly automatic, second-guessing can only slow that process. When the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex quietens, those doubts are cut off at the source. The result is liberation. We act without hesitation, creativity flows more freely, risk-taking becomes less frightening, and the whole combination lets us flow. Changes in brainwave functioning promote this process. In flow, we shift from the fast-moving beta wave of waking consciousness to the far slower borderline between alpha and theta.

Finally, there’s the neurochemistry of flow. A team of neuroscientists at Bonn University in Germany discovered that endorphins are part of flow’s hormonal cocktail, including norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide and serotonin. All five are pleasure-inducing, performance-enhancing neurochemicals that boost muscle reaction times, attention, pattern recognition and lateral thinking. This neurobiology tells us that we have probably cracked the optimal performance code (which is a big deal).

The Flow State

According to Csikszentmihalyi, ten factors accompany the experience of flow. While many of these components may be present, it is not necessary to experience all of them for flow to occur:

Clear goals that, while challenging, are still attainable.

The intense concentration and focused attention.

The activity is intrinsically rewarding.

Feelings of serenity, losing feelings of self-consciousness.

Timelessness: a distorted sense of time; feeling so focused on the present that you lose track of time passing.

Immediate feedback.

Knowing the task is doable, a balance between skill level and the existing challenge.

Feelings of having personal control over the situation and the outcome.

Lack of awareness of physical needs.

Complete focus on the activity itself.

If you are trying to achieve flow, it can help if a) you have a specific goal and plan of action, b) it is an activity that you enjoy or are passionate about, c) there is an element of challenge, d) you can stretch your current skill level (at least slightly).

Csikszentmihalyi explained that "flow happens when a person's skills are fully involved in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable. So, it acts as a magnet for learning new skills and increasing challenges." He added: "If challenges are too low, one gets back to flow by increasing them. If challenges are too great, one can return to the flow state by learning new skills."

References and Further Reading

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). The contribution of flow to positive psychology.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279-298). Springer, Dordrecht.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 239-263). Springer, Dordrecht.

Cheruvu, Ria. (2018). The Neuroscience of Flow. 10.13140/RG.2.2.12520.57608.

Christopher Peterson

Christopher Peterson (1950- 2012) was an American psychologist, the science director of the VIA Institute on Character and co-author (with Martin Seligman) of Character Strengths and Virtues (for the classification of character strengths). He was noted for his work in the study of optimism, health and well-being, and is one of the founders of positive psychology. Dr Peterson won the 2010 Golden Apple Award, the most prestigious teaching award at Michigan University.

Peterson produced two remarkable books that helped to establish the positive psychology movement. These are “A Primer in Positive Psychology” and “Character Virtues and Strengths” (with Martin Seligman). He wrote an ongoing blog for Psychology Today called The Good Life: Positive Psychology and what makes life worth living. When Peterson was asked for a concise definition of “positive psychology”, he said: “Other people matter, period.”

Sonja Lyubomirsky

Sonja Lyubomirsky (distinguished professor and vice-chair, University of California, Riverside) devoted most of her research career to studying human happiness. Her research addressed three critical questions: 1) What makes people happy? 2) Is happiness a good thing? 3) How can people learn to lead happier and more flourishing lives?

Drawing on her ground-breaking research with thousands of people, Sonja Lyubomirsky has pioneered a detailed yet easy-to-follow plan to increase happiness in our day-to-day lives. Her book The How of Happiness offers a comprehensive guide to understanding what happiness is and isn’t and what brings us closer to the happy life we picture for ourselves.

In her book, The Myths of Happiness, Dr Lyubomirsky draws on the latest scientific research to show that believing in happiness myths can have toxic consequences. Not only do our false expectations turn into a full-blown crisis, but they may steer us to make poor decisions and impair our mental health.

The Sustainable Happiness Model

The Sustainable Happiness Model (SHM - Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005) provides a theoretical framework for experimental intervention on increasing and maintaining happiness. According to this model, three factors contribute to an individual's long-lasting happiness: a) the inherent set point, b) life circumstances, and c) intentional activities or effortful acts that are naturally variable and episodic. Such activities, including acts of kindness, expressing gratitude or optimism, and savouring joyful life events, represent the most promising route to sustaining enhanced happiness.

Future researchers must learn which practices make people happier and how and why they do so. Despite several barriers to increased well-being, the model suggests that less happy people can strive successfully to be happier by learning various effortful strategies and practising them with determination and commitment.

The Happiness Pie Chart

The happiness pie chart was initially proposed in a 2005 paper by researchers Sonja Lyubomirsky, Kennon Sheldon, and David Schkade. The happiness pie chart depicts what contributes to our well-being. Unfortunately for some of us, the chart suggests, the genes we inherited from our parents significantly affect how fulfilled we feel. But it also contains good news: by engaging in healthy mental and physical habits, we can still control our happiness.

This pie chart has received lots of (valid) criticisms, and the authors of the chart agree with many of them. They explained that subsequent research had supported the most crucial premise of the Sustainable Happiness Model (SHM), which gave rise to the pie chart. In other words, individuals can boost and maintain their well-being through intentional behaviours. However, such effects may be weaker than we initially believed. They describe three existing models descended from SHM, i.e., the Eudaimonic Activity Model, the Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model, and the Positive Activity Model. Research testing these models has further supported the premise that how people choose to live makes a difference in their well-being.

Barbara Fredrickson

Barbara Fredrickson is a leading scholar in social psychology, affective science (the study of emotion) and positive psychology. Fredrickson’s work on studying positive emotions led to the development of Broaden and Build Theory. In 2013, Fredrickson released the book Love 2.0, which guides how to increase opportunities to receive and provide moments of love.

The work of Fredrickson and her colleagues has had a significant impact on the science of happiness. Their study of positive emotions, mainly “the big ten emotions” (i.e., love, joy, gratitude, serenity, interest, hope, pride, amusement, inspiration and awe), has given life to many happiness habits.

Building and maintaining strong relationships is directly linked to the need to care about friends and family and cultivate positive emotions in mutual experiences with them. The link between “caring” and positive emotions appears when we care for others, creating opportunities for developing and experiencing (micro instances of) love. This fact is seen through independent research that suggests the caring habit of volunteering often creates just as much, if not more positive emotion, within the volunteer than in those receiving the support.

Perhaps most closely connected would be Fredrickson’s study of gratitude and why it is an integral component of a positive mindset and happiness habit; “Gratitude opens your heart and carries the urge to give back, to do something good in return, either for the person who helped you or for someone else.” (Fredrickson, 2009).

Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions

Fredrickson's work on studying positive emotions, like love, began in 1998 and led to a theory on positive emotions called the Broaden and Build Theory. The substance of this theory lies in the notion that positive emotions play an essential role in our survival.

Positive emotions like love, joy, and gratitude promote new and creative actions, ideas and social bonds. When people experience positive emotions, their minds broaden, opening to new possibilities and ideas. At the same time, positive emotions help people build their well-being resources, consisting of physical, intellectual and social resources (Fredrickson 2009).

The building part of this theory is tied into the findings that these resources are durable and can be drawn upon later in different emotional states to maintain well-being. The theory also suggests that negative emotions serve the opposite function of positive ones. When threatened with negative emotions like anxiety, fear, frustration or anger, the mind constricts and focuses on the imposing threat (real or imagined), thus limiting one’s ability to be open to new ideas and build resources and relationships. Fredrickson draws on the imagery of the water lily to beautifully illustrate her theory: “Just as water lilies retract when sunlight fades, so do our minds when positivity fades” (Fredrickson 2009).

Barbara Fredrickson uses the term “positivity” to describe the experience of one or several positive emotions. Although each type of positivity feels unique and arises for different causes, they all subscribe to those same basic facts. The following are the facts worth knowing about positive emotions:

They don’t last long. Good feelings come and go.

They change how our mind works.

They transform our future. Although fleeting, their effect accumulates and helps us build physical, mental and social resources over time. In other words, they can create upward spirals of positivity and health in our lives.

They can stop the downward spiral of negativity. Positivity can undo the harmful effects of stress, anxiety and general negativity (see Losada’s Ratio).

We can increase our positivity

Fredrickson’s research has shown that positivity doesn’t simply reflect success and health. It can also produce success and health. It means that we can find traces of their impact even after our positive emotions fade. In other words, our positivity has lasting consequences in our lives. Positivity can be the difference between flourishing and languishing.

The Notorious Losada Ratio

In her 2009 book, Positivity, Fredrickson’s research defines positivity and how it can transform people’s lives. At the time, her research showed a 3 to 1 positivity ratio as a unique “tipping point” between flourishing and languishing, an ideal suggestion for high-functioning teams, relationships and marriages. This ratio was known as the “critical positivity ratio,” sometimes called Losada’s Ratio, as it was calculated in collaboration with Marcial Losada (a Chilean psychologist).

Fredrickson explained how the ratio of experiencing positive emotions to negative emotions (approximately 3 to 1) leads people to achieve optimal levels of well-being and resilience. This idea was a ground-breaking discovery in creating discussions on how a positive state of mind can enhance relationships, improve health, relieve depression and broaden the mind.

A 2013 study by Nicholas Brown, Alan Sokal, and Harris Friedman challenged the validity of Losada’s Ratio. Their concerns stemmed from an empirical viewpoint. They did not find any problem with the idea that positive emotion is more likely to build resilience or that a higher positivity ratio is more beneficial than a lower one. They found an issue in assigning applications of mathematics to pinpoint that specific ratio (Brown et al., 2013).

Fredrickson responded to the criticism by agreeing that more study is necessary to designate a precise mathematical value/ratio; however, she stood firm that her research has adequately proved that the benefit of a high positivity to negativity ratio is solid: “Science, at its best, self-corrects”. We may now witness such self-correction as mathematically precise statements about positivity ratios give way to heuristic statements such as “higher is better, within bounds.” (Fredrickson, 2013). The door is open for further scientific study, and more data will come with time.

Love 2.0

Barbara Fredrickson released her book Love 2.0 (2013), which serves as a guide to learning how to increase opportunities to receive and provide moments of love. Fredrickson described love as an emotion that, like all other emotions, is momentary, not enduring, and can be experienced in micro-moments (micro-doses).

Through this lens, love is not an emotion for just soul mates and family ties. Love 2.0 defines love as an emotion that can be shared with family members and strangers several times a day. Fredrickson found that the song “What a Wonderful World”, made famous by Louis Armstrong in the 1960s, fit her theory: “I see friends shaking hands….sayin’ ‘how do you do?’ / they’re really saying...’ I love you’” (Fredrickson 2013).

Fredrickson described (2013) love as a momentary emergence of three tightly interwoven events: first, a sharing of one or more positive emotions between you and another; second, synchrony between yours and the other person’s biochemistry and behaviours; and third, a reflected motive to invest in each other’s well-being that brings mutual care. Then, a moment of love is created when these criteria are met. When a person finds another with whom they can share several such moments, bonds are formed, loyalty is developed, and enduring relationships are created.

The Vagus Nerve and Social Connectivity

The vagus nerve (X cranial nerve or 10th cranial nerve) runs from the brain through the face and thorax to the abdomen and is a central component of our parasympathetic nervous system. A healthy vagal tone signals your body to click into the "Tend-and-Befriend or Rest-and-Digest” mode and turns off the "Fight-or-Flight" mechanism driven by the sympathetic nervous system.

Frederickson and Kok (2016) observed how well the vagus nerve functioned in various individuals. They found that a higher vagal tone is linked to activation of the vagus nerve and parasympathetic response and was better at self-regulating emotions. They hypothesised that a higher vagal tone was directly related to people’s ability to experience more positive emotions, increasing positive social connections. Having more social links would, in turn, increase vagal tone, thereby improving physical health and creating a positive cycle and self-perpetuating "upward spiral".

Upward Spiral Theory

In 2018, Fredrickson and Joiner published a paper reflecting on their 2002 article, which provided empirical support for their upward spiral hypotheses. Their conjecture was based on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, which states that experiences of momentary mild positive emotions broaden people’s awareness and, over time, build substantial personal resources that contribute to their overall emotional and physical well-being.

They highlighted empirical and theoretical advancements in the scientific understanding of upward spiral dynamics associated with positive emotions, focusing on the new upward spiral theory of lifestyle change (Positive Emotions Trigger Upward Spirals Toward Emotional Well-Being).

The primary contribution of Fredrickson and Joiner (2002) was to demonstrate that everyday positive emotions (as fleeting as they are) can initiate a cascade of psychological processes that carry an enduring impact on people’s subsequent emotional well-being. Beyond making people feel good in the present, positive emotions also appear to increase the odds (through dynamic broaden-and-build processes) that people will feel good in the future. A strength of this study was its prospective design over five weeks.

Research has shown that healthy behaviours experienced as pleasant are more likely to be maintained. The upward spiral theory unpacks this relation, emphasising automatic, often nonconscious motives and mental and social resources that make people more sensitive to subsequent positive experiences. To the extent that positive affects (emotions) are experienced during a healthy behaviour, the upward spiral theory suggests that they create unconscious motives, which grow stronger over time as they are increasingly supported by the resources (both biological and psychological) that are built by positive affects.

Downward Spiral of Negativity

It’s a fact that the patterns of negative thinking breed negative emotions (and vice versa), so much so that they can even spiral down into pathological states, such as depression, phobias or obsessive-compulsive disorders. The reciprocal dynamic between negative thoughts and emotions is why downward spirals are so slippery. Negative thoughts and emotions feed on each other and pull us down into their gloomy abyss of negative states.

A downward spiral is often described as a depressive state where the person experiencing the downward spiral is getting more and more depressed, perhaps due to unknown causes. It is called a spiral because there seems to be no way to stop it.

Ed Diener

Ed Diener is a professor of psychology at the University of Utah and the University of Virginia. His research is focused on the theories and measurement of well-being, temperament and personality influences on well-being, income and well-being, cultural impacts on well-being and how employee well-being enhances organisational performance.

Dr Diener has co-edited three books on subjective well-being. 1) Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, 2) Advances in Quality-of-Life Theory and Research, and 3) Culture and Subjective Well-Being.

He coedited the Handbook of Multimethod Measurement in Psychology and wrote a popular book on Happiness with his son, Robert Biswas-Diener, and co-author of Well-Being for Public Policy.

Ilona Boniwell

Professor Ilona Boniwell, mentored by Martin Seligman, founded and directed the first Master of Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) at the University of East London. She currently leads the International Master of Applied Positive Psychology (I-MAPP) at the University of Anglia Ruskin (the United Kingdom and France), teaches Positive leadership at École CentraleSupélec, conducts research in collaboration with École Head of Economics in Moscow and writes a monthly column for the magazine: Positive Psychology.

Dr Boniwell obtained her doctorate at Open University in England in 2000 and has taught at Oxford Brookes University and City University. She has written or participated in writing nine books and numerous scientific articles. She is the founder and first president of the European Network of Positive Psychology (ENPP), where she was a member of the Management Committee for many years.

Dr Boniwell became an active member of the French and Francophone Association of Positive Psychology in Paris. In 2012, she brought her expertise to the government of Bhutan to develop a policy based on the people's happiness at the UN's request. In addition to her academic work, she is passionate about the practical applications of Positive Psychology in companies, education and coaching.

As director of Positran (a consulting company specialising in the application of fundamental methods of psychology), she works with her team in commercial companies and educational institutions around the world (France, United Kingdom, Iceland, Netherlands, Portugal, China, Singapore, Japan, etc.) to effect a lasting positive transformation. She has also developed a complete Wellbeing and Positivity at Work kit for the Government of Dubai.

Kate Hefferon

Dr Hefferon is a chartered research psychologist and an honorary reader at the University of East London. She has dedicated her academic studies to understanding the role of the body in well-being across various populations, topics and interventions. Dr Hefferon’s PhD thesis was on the experience of post-traumatic growth among female breast cancer survivors and the role of the body and physical activity in the recovery and growth process.

Dr Hefferon became the Programme Leader of the world-renowned Master in Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) at the University of East London (UEL). She founded and led the posttraumatic growth research unit at UEL and continues her affiliation with the Masters in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology (MAPPCP) at UEL.

Dr Hefferon’s research interests mainly focus on post-traumatic growth and the body and physical activity within clinical populations. She also took up a post at the University of the Arts, London College of Fashion, to pursue her interest in connections between clothing practices, the body, and wellbeing.

Another area in which Dr Hefferon is passionate about is qualitative approaches within the psychological sciences. She is an expert in qualitative research with over a decade of experience in facilitating, training and supervising novice and advanced researchers across various qualitative approaches. She co-founded the Scottish Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Group (SIPAG), was a former co-facilitator of the London Regional IPA group and co-founded London IPA training.

Dr Hefferon is a member of the British Psychological Society (Division of Teachers and Researchers in Psychology), a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (Advance HE) and the Royal Society of Arts, a senior associate member of the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) and a founding member of the Advisory Board for the European Network of Positive Psychology.

Itai Ivtzan

Dr Itai Ivtzan is a positive psychologist, a senior lecturer and the program leader of MAPP (Masters in Applied Positive Psychology) at the University of East London (UEL). He is also an honorary senior research associate at University College London (UCL). He has published many books, journal papers and book chapters. His main research areas are spirituality, mindfulness, meaning and self-actualisation.

For many years, Dr Ivtzan has run seminars, lectures, workshops and retreats in the UK and worldwide, in various educational institutions and private events while focusing on different psychological and spiritual topics such as positive psychology, psychological and spiritual growth, consciousness and meditation.

Dr Ivtzan is confident that meditation can positively transform individuals and even the whole world. Accordingly, he has invested much time in studying, writing about, and teaching meditation.

Dr Ivtzan is also a qualified psychotherapist offering Awareness Coaching (a couple of sessions) and Awareness Therapy (many sessions) to help his clients remove unconscious blocks and achieve their full potential.

He is the author/co-author of Awareness is Freedom: The Adventure of Psychology and Spirituality, Mindfulness in Positive Psychology: The Science of Meditation and Wellbeing, Second Wave Positive Psychology: Embracing the Dark Side of Life, and Applied Positive Psychology: Integrated Positive Practice.

Time Lomas

Dr Lomas is a lecturer in positive psychology at the University of East London, trying to drive the field of positive psychology into new and uncharted territories. Before being a positive psychology scholar, he was a singer in a Ska Band (a music genre that originated in Jamaica in the late 1950s and was the precursor to rocksteady and reggae), a psychiatric nursing assistant, and an English teacher in China.

Dr Lomas’ research and scholarly activities have produced 70 peer-reviewed journal papers and eight books (to 2020). He has focused his academic contributions on three main areas: mindfulness, positive psychology theory and cross-cultural lexicography.

Dr Lomas played a significant role in developing MAPP (Masters in Applied Positive Psychology) at the University of East London (UEL), including serving as an associate programme leader responsible for distance learning (2014-2015). He has published the following books (as the author or the co-author).

Lomas, T., & Huett, A. (2019). Happiness: Found in Translation. Tarcher: New York.

Lomas, T. (2018). Translating Happiness: Enriching our Experience and Understanding of Wellbeing through Untranslatable Words. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Lomas, T. (2018). The Happiness Dictionary: Untranslatable Words from Around the World to Help us Lead a Richer Life. London: Piatkus.

Lomas, T. (2016). The Positive Power of Negative Emotions: How to harness your darker feelings to help you see a brighter dawn. London: Piatkus.

Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second Wave Positive Psychology: Embracing the Dark Side of Life. London: Routledge.

Lomas, T. (2014). Masculinity, Meditation, and Mental Health. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied Positive Psychology: Integrated Positive Practice. London: Sage.

Paul Wong

Dr Wong is the professor emeritus of Trent University (Ontario, Canada), a fellow of the American Psychological Association (APA) and the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), President of the International Network on Personal Meaning (www.meaning.ca) and the Meaning-Centred Counselling Institute. He is the architect of Meaning-Centred Counselling and Therapy (MCCT), an integrative existential positive approach to counselling, coaching and psychotherapy. Dr Wong is also the editor of the International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology.

Dr Wong’s story is one of transformation and triumph despite tragedy. He started his life as a melancholic child in China, who grew into an impoverished refugee in Hong Kong and later a sincere convert to Christianity and a mistreated minister in Toronto. Dr Wong is now an influential professor and psychologist on the world stage who has spoken in multiple cities across four continents.

What are his survival and success secrets in this harsh and turbulent world? Dr Wong’s answer may be surprisingly simple, yet complicated: the pursuit of meaning! “There is no other motivation more powerful and more transformative. All my life, day in and day out, sunshine or storm, paid or unpaid, healthy or sick and even now in my old age, I have struggled in my quest for meaning with little reward or recognition. What has sustained me is the deep conviction that I can bring meaning and thus happiness to the suffering masses.”

Paul Wong is one of the pioneers who extended the second wave of positive psychology (PP 2.0) to Existential Positive Psychology (EPP) by formally incorporating the dialectical principles of Chinese psychology, the bio-behavioural model of adaptation and cross-cultural positive psychology.